In a quiet nook of a library at Mississippi State College, you’ll discover a slim purple quantity that tells the story of what could also be America’s first Juneteenth. It passed off in New Orleans in the summertime of 1864 to have a good time the day of liberation for the enslaved folks dwelling within the 13 Louisiana parishes exempted from President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, issued the earlier January. It was truly a collection of celebrations—or jubilees, as these have been identified—over two extraordinary months, with the biggest occurring on June 11, a month after the Free State Conference abolished slavery throughout Louisiana.

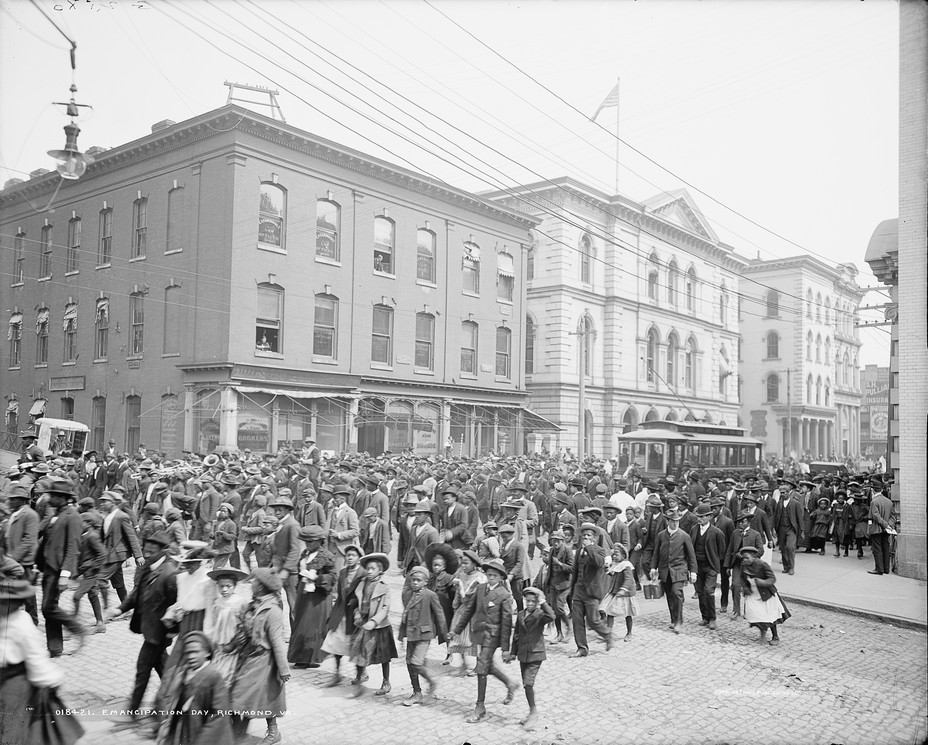

Newly freed New Orleanians gathered in mass public conferences—celebrations, parades, church providers, and shows of Black arts and sciences—of the sort that had been banned underneath slavery. Every gathering introduced collectively the town’s Black neighborhood—the just lately emancipated and people already free—to have a good time a way forward for citizenship, sacrifice, studying, and social development. In doing so, they confirmed themselves and the broader world that they have been a united neighborhood, prepared to guard their households, demand financial justice, and declare their rightful place as residents.

Juneteenth—generally known as America’s second Independence Day—takes its identify from June 19, 1865, when the U.S. Military in Galveston, Texas, posted a proclamation declaring the enslaved free. In 1866, Black Galvestonians gathered to commemorate the date of their freedom, starting an annual observance in Texas that unfold throughout the nation and have become a federal vacation in 2021. However the slender quantity within the Mississippi museum, and the summer-long celebrations in New Orleans that it information, invitations us to appreciate that Juneteenth was a nationwide vacation from the beginning.

In January 1863, Black New Yorkers celebrated the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation with a jubilee at Cooper Union, simply as African People did in Chicago and different cities throughout the North that yr. However in New Orleans, they held what often is the first recorded mass celebration—the primary Juneteenth—organized by previously enslaved folks rejoicing on the finish of their very own enslavement. Different such celebrations adopted. In April 1865, for instance, 1000’s of Black South Carolinians paraded by means of Charleston, celebrating the evacuation of Accomplice forces and their very own emancipation. And in June 1866, in fact, Galvestonians started the commemorations that grew to become a nationwide vacation.

Accounts from New Orleans in the summertime of 1864, in a metropolis that was as soon as the nation’s largest slave market, verify that the second of liberation was America’s second Independence Day—and as in 1776, it marked the start of a combat, not the top. New Orleans’s celebrations have been the primary battle cry in African People’ battle to attain one thing greater than freedom.

Learn: The reality about black freedom

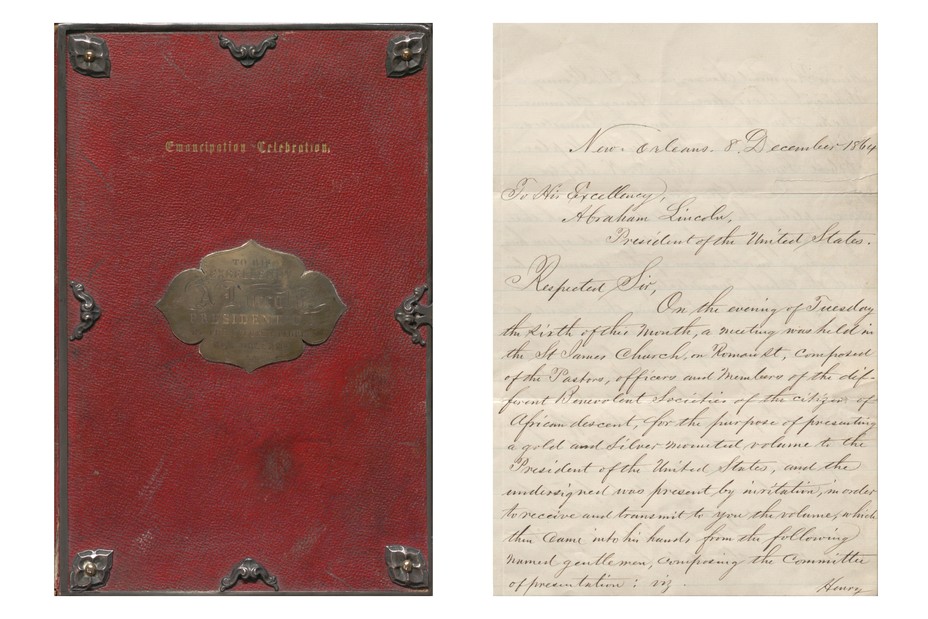

On the finish of the summer season, 10 previously enslaved males determined to publish a historical past of the summer season’s occasions, the story discovered within the skinny quantity. Their pamphlet was a direct rebuke of state legal guidelines banning enslaved folks from studying to learn or write, a lot much less voicing their calls for in print. This particular quantity—which demonstrated the authors’ academic accomplishments and their abilities as printers and editors—was designed to encourage a person they thought-about an ally, although generally a reluctant one. We don’t know what number of copies of Emancipation Celebration they printed in 1864; few exist at present. However this one, expensively certain in purple leather-based with silver edging, probably survived as a result of, because the brass plate on its cowl reveals, it was a present to His Excellency A. Lincoln from the Free Coloured Individuals, New Orleans.

The most important of the occasions it recorded began on June 11 in Congo Sq.—a Black house used for generations for celebrations, commemorations, and markets—after which expanded with a parade by means of the French Quarter. It drew troopers from the Louisiana Native Guard and U.S. Coloured Regiments, who marched alongside kids from a number of African American colleges, adopted by members of Black commerce and charitable organizations. The audio system’ platform featured educators from the town’s Black colleges and African American veterans of the Warfare of 1812. They have been seated alongside two white leaders, Normal Nathaniel P. Banks and Louisiana Governor Michael Hahn, who each arrived late. This was not merely a celebration of emancipation. The planners had organized demonstrations of the function that African People had performed in destroying slavery and their health for the tasks of citizenship that ought to observe.

The 2 featured audio system that day have been each leaders throughout the Black neighborhood. Stephen Walter Rogers had been enslaved as a toddler however freed in his teenagers. By 1864, he was one of many best-known Black spiritual leaders within the metropolis. Francois Boisdoré was born free to previously enslaved dad and mom and grew up as a member of New Orleans’s elite Creole neighborhood. By the point of the town’s jubilees, Boisdoré was working as an educator and a bookkeeper. He had battled Hahn within the press over Black suffrage, and suspected that Banks’s help for Black schooling was extra about making certain a provide of productive laborers than constructing an expert class.

Each Rogers and Boisdoré opened with thanks and reward for Lincoln, Banks, and Hahn, however reminded their viewers that extra have to be finished. Rogers insisted that African People wished solely 4 key issues: “Freedom, Suffrage, Work, and Wages.—Give him these 4 needs and it makes him a citizen in each sense of the phrase.” With that freedom, Rogers reminded his viewers, African People didn’t search to carry workplace, however to “say by our sacred votes whom we will need to rule over us.” If these 4 needs have been granted, “we are able to say that slavery is completed perpetually; however not till then.”

Boisdoré addressed the viewers in French. He had two messages, one for the Black neighborhood and one other for the civil and navy commanders onstage. Addressing “my emancipated brothers,” he argued that the trail to actual freedom ran by means of work and schooling. A few of his arguments mirrored Nineteenth-century ideas of uplift, that Black males needed to show that they have been industrious and clever to be worthy of citizenship. Nevertheless, Boisdoré was not solely excited about convincing white People that Black People have been able to self-government. He was additionally involved with the way forward for Black households and Black communities. Earlier than emancipation, slave house owners stole enslaved folks’s labor, overrode their free will, and ripped households aside by promoting kids away from their dad and mom. Now that these horrors have been over, Boisdoré argued, freed folks lastly would wish to work, as a result of they might use their labor to safeguard their households and future. Work, he declared, would supply the laborer “with technique of consolation and ease for himself and his household” and allow Black households “to carry up their kids and provides them an excellent schooling.”

However then Boisdoré went additional. The place Rogers had pushed just for male suffrage, Boisdoré insisted that those that as soon as oppressed Black New Orleanians should “acknowledge and make sure to all and each one the suitable of citizenship—their proper to be electors, and consequently their proper to be additionally themselves elected.”

Jubilees introduced Black New Orleanians collectively again and again that summer season to listen to and specific messages concerning the significance of schooling, citizenship, and financial justice. Within the course of, contributors started to topple the practices that had held up the establishment of slavery. As soon as barred from talking in public, Black leaders turned to the state’s governor and demanded extra. Beforehand banned from giant gatherings, Black New Orleanians pushed past Congo Sq. and paraded by means of the town’s streets. Now the house owners of their labor, Black artisans displayed their wares, and congregations listened to messages about Black enterprise.

Through the summer season’s closing gathering, New Orleanians got here collectively to display the depth and breadth of their talents. On August 1, a parade of individuals carried examples of their “trades and home arts” from a Black church to the identical room above metropolis corridor the place the state emancipation ordinance had handed in Could. There, members of the general public may see shows of and prizes for Black portray, sculpture, and pictures; literature; needlework and dressmaking; dentistry and midwifery; and meals and manufactured items of all types. The assemblage of the “specimens of business of the coloured folks” despatched a message that Rogers made express in a speech on the opening of the exhibition. Enslaved labor had constructed the nation’s financial may—and now Black artisans have been prepared to make use of their abilities to advertise Black folks’s welfare. Rogers proposed one other truthful, with delegations from each state, to lift $50,000 to help poor Black folks at dwelling and overseas.

The New Orleans organizers noticed themselves inside an extended historical past of Black-freedom actions. The occasion on August 1, for instance, commemorated Emancipation Day, a vacation recognizing the abolition of slavery within the British Caribbean that was celebrated all through the African diaspora within the mid-Nineteenth century. For enslaved folks throughout the Civil Warfare South, authorized freedom adopted a halting and precarious path. Juneteenths arrived again and again, however these emancipation celebrations have been solely the start. Because the audio system that summer season in New Orleans knew, Black liberation was an unfinished course of.

However the query stays: Why give this unprecedented assortment of speeches and celebrations to Lincoln? What did Black New Orleans leaders search from the president? They praised him at instances, however in addition they critiqued his lengthy help of colonization together with the unequal pay that Black troopers nonetheless acquired that summer season, and Lincoln had not but spoken publicly about his new help for restricted Black male suffrage.

A tiny booklet in a close-by museum case gives a doable reply, or a minimum of a clue. Not removed from Emancipation Celebration on the Frank and Virginia Williams Assortment of Lincolniana at Mississippi State College sits a uncommon pocket-size copy of the Emancipation Proclamation. The industrialist and abolitionist John Moore Forbes had 1 million copies printed and shipped to Union armies so troopers may distribute them to enslaved folks. These little copies dropped at troopers and enslaved alike the textual content of the president’s proclamation, which formally confiscated folks enslaved in Accomplice territory as a wartime measure and allowed freedmen to hitch the Union Military, however didn’t finish slavery or lengthen citizenship. The Proclamation was enforced solely in territory managed by federal forces, and didn’t apply to folks already underneath federal jurisdiction when it was issued, together with New Orleanians. The Emancipation Proclamation alone didn’t finish slavery.

The copy of Emancipation Celebration addressed to Lincoln incorporates a closing web page that speaks to those limitations. The printer inserted a replica of an article from an area Unionist newspaper, The New Orleans Period, mentioning the variations between emancipation in Louisiana and elsewhere. The article proclaimed that emancipation in New Orleans was probably the most exceptional of all emancipation acts as a result of it introduced a authorized finish to the establishment of slavery, clearly and elegantly stating that “slavery and involuntary servitude … are hereby perpetually abolished and prohibited all through the state … The legislature shall make no legislation recognizing the suitable of property in man.” Whoever printed and certain the copy supposed for Lincoln wished the president to know that in Louisiana, slavery was no extra.

Learn: Six important reads to grasp Juneteenth

On December 6, 1864, a “committee of presentation” composed of Black New Orleans spiritual and civic leaders, together with Rogers and Boisdoré, invited Thomas J. Durant, an area white lawyer and abolitionist, to hitch them at St. James African Methodist Episcopal Church on Roman Avenue. They offered him with Emancipation Celebration and requested that he ship it to the president. In a letter accompanying the present, Durant assured the president that these males represented “a most worthy, loyal and patriotic portion of our inhabitants” who had “testified to their devotion to the Authorities by sacrifice of the very best character.” They gave this present to Lincoln with “probably the most heartfelt devotion and gratitude to the nation.”

The committee members despatched the quantity to Lincoln by means of a white middleman, figuring out that doing so elevated the possibilities that Lincoln would see it himself. However did Lincoln learn the quantity? We all know that the White Home acquired it and that Black New Orleanians acquired Lincoln’s letter of thanks, however one among his secretaries could have accepted the present and written that acknowledgment. It’s arduous to know if Emancipation Celebration helped persuade the president to do extra to advance Black citizenship.

Regardless, Lincoln’s views on Black citizenship have been already evolving. He arrived in Washington as a longtime opponent of human enslavement, however he had additionally spoken brazenly towards African American suffrage and civil rights. By 1864, nonetheless, Lincoln was insisting to his Cupboard and his get together that they need to discover a method to completely destroy slavery. Simply days earlier than the June 11 celebrations in New Orleans, Republicans unveiled their platform for the 1864 presidential marketing campaign, which included a constitutional modification abolishing slavery.

Lincoln had additionally begun to talk privately with members of his Cupboard and different politicians concerning the prospects of restricted Black male suffrage. By the next spring, simply days earlier than his assassination, Lincoln was so assured in these views that he shared them publicly. On April 11, 1865, addressing a crowd exterior the White Home, Lincoln argued that “very clever” African People and “those that serve our trigger as troopers” had earned the suitable of suffrage. It was a radical step for the reasonable and masterful politician. Black navy service and Black civic leaders, together with some from New Orleans who had debated and mentioned emancipation and civil rights with Lincoln throughout their visits to the White Home, had modified his considering on the justice of Black citizenship.

The red-bound quantity discovered a becoming dwelling in Mississippi, a state that embodies the probabilities and failures of the second the pamphlet commemorates. Half of the state’s inhabitants was enslaved in 1860; by the 1870s, Mississippi had quite a few Black sheriffs, justices of the peace, attorneys, and businessmen, and the primary two African American U.S. senators. However the state’s ugly postwar historical past additionally demonstrates the offended dedication to restrict emancipation’s hopeful legacy by means of race riots, authorized trickery, and homicide.

The 1000’s of Black New Orleanians who celebrated slavery’s finish collectively, the Black leaders who stood onstage and demanded extra from white politicians, and the ten Black males who oversaw the pamphlet’s printing wished the president and the nation to know that their state had finished one thing extraordinary—it had ended slavery. Additionally they wished folks to know that the work was removed from over. It’s a lesson that extends from the very first Juneteenth to the current day. Ending slavery didn’t finish injustice; it was only one extra step within the journey towards freedom and equality.

0 Comments